Normal-mass SMBH in the Early Universe

A population of normal or undermassive black holes at high-z galaxies, highlighting a critical selection bias.

Research Highlight: Solving the “Overmassive” Black Hole Puzzle

One of the deepest questions in astronomy is how supermassive black holes (SMBHs) and their host galaxies grow together. In the nearby universe, we see a tight link: the bigger the galaxy, the bigger its central black hole. This is known as the $M_{BH}-M_{*}$ relation, and it’s a cornerstone of galaxy-SMBH co-evolution theories.

With the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), we can finally test this relationship in the early universe. But the initial results were baffling. Many studies found black holes at high redshift that were “overmassive”—far too large for their host galaxies when compared to our local standards.

This created a major puzzle: Did black holes grow first and their galaxies had to catch up? Or was something else going on?

The Problem: A Pervasive Selection Bias

We suspected this “overmassive” trend might be an illusion, a product of selection bias.

- Luminous Quasar Bias: If you search for the brightest AGNs, you will naturally find the most massive black holes, which are often “overmassive” compared to their hosts.

- Faint AGN Bias: If you search for fainter AGNs in low-mass galaxies, you face a different problem. The “broad lines” become fainter and narrower, making them incredibly difficult to distinguish from galactic “outflows”.

Both effects would bias samples, leaving a critical part of the black hole population hidden.

The Investigation: A New Strategy

Our study was designed to overcome these biases. Instead of hunting for AGNs directly, we started with a well-defined sample of galaxies.

We used the ALPINE-CRISTAL-JWST survey to target 18 representative, high-mass ($M_{*}>10^{9.5}M_{\odot}$) star-forming galaxies at $z=4.4-5.7$. Our simulations showed this high-mass range is a “sweet spot”: it’s where we could detect “normal” mass black holes, if they existed.

Our key tool was the NIRSpec Integral Field Unit (IFU) on JWST. This allowed us to get a complete “data cube” for each galaxy, spatially separating the central nucleus from the light of the host galaxy. We developed a meticulous spectral fitting pipeline to hunt for faint, broad H$\alpha$ emission, carefully using the [OIII] line to model and rule out contamination from outflows.

Key Findings

1. A Population of “Normal-Mass” Black Holes

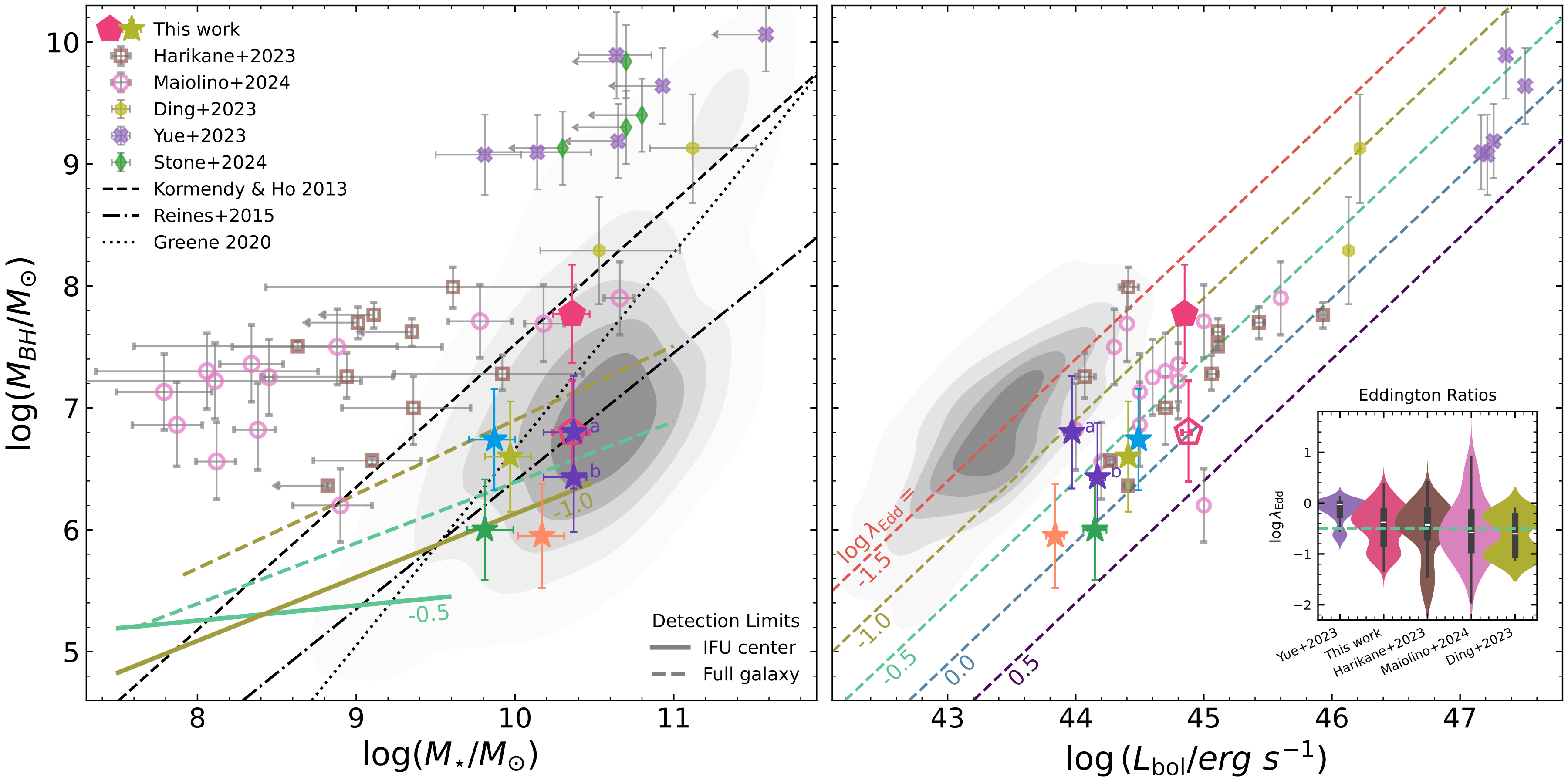

We identified 7 broad-line AGN candidates across our sample. Their black hole masses range from $10^{6}$ to $10^{7.5}$ solar masses.

The main result is shown in the figure below. Unlike previous studies, our AGN candidates (stars and pentagon) *lie close to or below the local $M_{BH}-M_{}$ relations** (the dashed and dotted lines). This is the first sample at this redshift to not appear overmassive. It strongly suggests that the “overmassive” trend seen before was a direct result of selection bias.

2. One Robust AGN and Six Fainter Siblings

Our sample includes one “highly robust” AGN, DC_536534. It shows a textbook broad H$\alpha$ line with a width of ~2800 km/s. Thanks to the IFU, we could prove that this broad emission comes from an unresolved, point-like source at the galaxy’s center—exactly as expected for an AGN—while the narrow emission comes from the extended host galaxy.

The other six candidates are fainter, with broad lines of 600-1600 km/s. These are precisely the types of AGNs that are easily missed or mistaken for outflows in surveys with lower signal-to-noise or without spatial information.

3. Standard Diagnostics Fail at High Redshift

We also tested if these AGNs could be found using standard emission-line ratio diagnostics (like the BPT diagram). The answer was a clear “no.” All 7 of our candidates, including the most robust one, fall into the “composite” or “star-forming” regions of these diagrams. This confirms that these traditional tools are unreliable at high redshift.

4. High AGN Fraction in Massive Galaxies

We find a broad-line AGN fraction between 5.9% (robust only) and 33% (all candidates) in these galaxies. This relatively high fraction is likely because we focused on high-mass galaxies where detection is more feasible. We also found a strong link to galaxy interactions: 5 of our 7 candidates (including a dual-AGN system) are in merging or clumpy galaxies, suggesting these interactions may be helping to fuel the black holes.

Overall Conclusion

Our study provides a new perspective on black hole growth in the early universe. By using a galaxy-selected sample of high-mass galaxies, we unveiled a population of “normal” and even “undermassive” black holes that were missed by previous surveys.

This finding demonstrates that the “overmassive” black hole puzzle is likely an illusion created by strong, mass-dependent selection biases. The fundamental relationship between black holes and galaxies appears to have been in place very early in cosmic history, with potentially little evolution from $z\sim5$ to today.

Resources

- Paper: Ren, W., et al. 2025, MNRAS